Supporting Development

by Melanie Ferris/Huntinghawk

by Melanie Ferris/Huntinghawk

“Aboriginal people believe that children do not belong to us but are gifts sent from the Creator. It is our job to nurture and guide children throughout their childhood so they will grow to fulfill their purpose while on earth. Because children are so sacred, it is everyone’s responsibility to nurture them and keep them safe, to provide them with unconditional love and attention so they will know they are wanted and hold a special place in the circle. Every child regardless of age or ability has gifts and teaches us a lesson. They are all unique and should be respected”

(Best Start Resource Centre, 2006, p. 19).

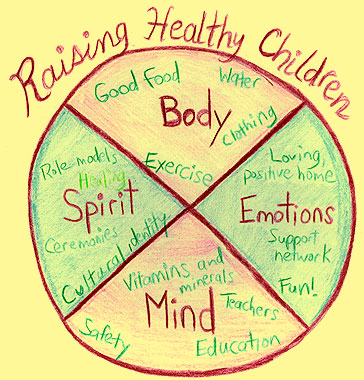

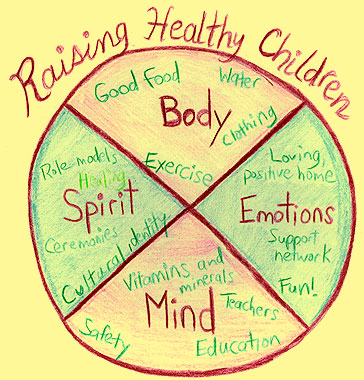

- The Aboriginal approach to early child development is holistic and includes all areas of development within the child as represented by the medicine wheel. The four areas of the circle represent the following areas of development:

- Physical

- includes motor development, sleep, body weight, nutrition, medical care, and physical environment

- Mental - includes cognitive and language development

- Emotional - includes social and emotional development including self-confidence and a sense of belonging

- Spiritual - includes the child’s relationship to her self, family, nation, land, animals and the spirit world

(Best Start Resource Centre, 2006)

Although many factors have contributed to the challenges in the health and healthy development of some Aboriginal children, not all face these challenges. And when an Aboriginal child is given the opportunity to learn her language, customs and traditions through respectful and nurturing environments, she is more likely to develop resiliency (Best Start Resource Centre, 2006). Aboriginal parents need to be supported in reclaiming their parenting skills and traditions. Non-Aboriginal early childhood programs need staff and curriculum that incorporate Aboriginal cultures in a respectful way that must be evident in practice (Ball, 2008; OECD, 2004). This should include learning from Elders, traditions, ceremonies and families (Ball, 2008; Best Start Resource Centre, 2006; CCL, 2007).

|  |

Supporting LGBTQ Families

While LGBTQ families in Canada currently enjoy unprecedented social and legal recognition, this is a relatively recent development. However, despite these advancements, LGBTQ people still face considerable discrimination. As such they often access programs and services hesitantly, not knowing how they will be treated, and fearful to disclose their sexual orientation, gender identity or family structure.

Welcoming LGBTQ people and families into programs and services can be both simple and complicated. Some characteristics of LGBTQ-friendly programs or services include:

- Program or service policies and procedures that explicitly support LGBTQ inclusion.

- Intake forms that are inclusive of different family structures.

- A physical environment that reflects different family structures. This may include posters, books and magazines that reflect gender, sexual and family diversity.

- Service providers that are open and have the desire to know the people and families they serve.

- Service providers that recognize partners or other significant people as co-parents or family members.

- Service providers that use non-biased, inclusive language and open-ended questions that create a safe environment.

- Service providers that comply with the Ontario Human Rights Commission (www.ohrc.on.ca) and remind others that regardless of personal beliefs, their publicly-funded programs are open to all regardless of race, ancestry, place of origin, colour, ethnic origin, citizenship, creed, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, age, marital status, family status or disability.

For more information on supporting LGBTQ families, refer to Welcoming and Celebrating Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity in Families: From Preconception to Preschool. www.beststart.org/resources/howto/pdf/LGBTQ_Resource_fnl_online.pdf

Cultural Considerations

Stressors Faced by Newcomers

There are many reasons why people come to Canada. Some immigrate based on the promise of a brighter future for families. Others leave their homeland because of persecution or war. To leave a home country and transition to a new one, often with a different language and set of customs, can be very stressful. Although this major life transition may at first be exciting, all newcomer families experience "acculturative stress" (Neufeld et al., 2002, p. 752).

- Newcomers may face a multitude of stressors which in turn can impact the development of children born prior to or after the parent's arrival in Canada. These can include:

- Unemployment and underemployment

- Poverty

- Social exclusion, isolation

- Racism, discrimination

- Language and education challenges, such as waiting for English classes or the need to retrain or recertify

- Challenges accessing services due to language barriers, cost, transportation, social stigma, beliefs, lack of knowledge about services and understanding of services

- Lack of culturally appropriate services

- Altered expectations for women, such as having to fulfill traditional roles, new roles and added caregiver burdens without the support of extended families

(Berry, 2001; Cheong et al., 2007; National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health, 2008a; Neufeld et al., 2002; Oliver et al., 2007; Phinney et al., 2001; Thomas, 1995)

- Understanding Cultural Differences

Childrearing practices across cultures share

these broad goals:

- To promote the child's physical well-being

- To promote the child's psycho-social well-being

- To provide children with the competencies necessary for economic survival in adulthood

- To transmit the values of their culture

|

|

Families are the first and most important channel for the transmission of culture. Culture and family characteristics affect both resilience and vulnerability in the healthy development of young children (Melendez, 2005). Childrearing practices are embedded in the culture and determine behaviours and expectations surrounding childhood, adolescence, and the way children parent as adults (Small, 1998).

A lack of understanding of the various childrearing practices can lead to tension between the dominant culture, often represented by professionals, and the practices of a family. How families or caregivers raise their children varies across cultures. For example, the parenting values of Western societies give importance to independence such as the ability to problem solve independently, being assertive and inquisitive. In contrast many non-Western societies value interdependent attributes such as cooperation, respect for authority and sharing. In some cultures, parenting is assumed by a single individual, usually the mother, while at the other end of the continuum a child may have multiple caregivers, and any adult can assume the caregiving role.

- Different practices are particularly noticed in:

- Feeding practices

- Sleeping arrangements

- Verbal interactions

- Eye contact

- Interactions between children and adults

Ultimately, every parent wants a healthy and thriving child. As Small (1998) indicates, "no parenting style is 'right' and no style is 'wrong.' It is appropriate or inappropriate only according to the culture." (p. 108).

Responding to Cultural Differences

The first step in addressing possible cultural differences in an early childhood is to be aware of these specific cultural differences in parenting or care. For example, professionals need to "recognize that co-sleeping is an accepted practice in most parts of the world" (Gonzalez-Mena & Bhavnagri, 2001, p. 92), and that some may consider common North American child care practices the "very opposite of good care"

(Gonzalez-Mena & Bhavnagri, 2001, p. 92).

Navigating through some of these cultural differences in parenting and child care is not simple, and requires great sensitivity. Early years professionals need to openly communicate with parents, in order to build a solid rapport and trust (Okagaki & Diamond, 2000). Parents need to feel that their views have been heard and understood. Dodge, Colker, and Heroman (2002) suggest the following ways to constructively address these differences in the early childhood setting:

- Seek to understand the family's position – Ask open-ended questions to learn what concerns the parents may have.

- Validate the family's concerns and wishes – Restate what you hear them say to be sure you understand and to let the family know you hear them.

- Explain how your program addresses the family's concern – Acknowledge that there are different points of view on any topic. If possible, share research on topics of concern to parents and evidence-informed risk factors associated with the behaviour of concern to the professional.

- Make a plan to check in with one another to assess progress.

Finally, newcomers to Canada often rely on both formal (e.g., professionals) and informal (e.g., relatives, friends) social networks to access support services (Neufeld et al., 2002). Not surprisingly, newcomers tend to start with their informal networks, where typically a relative or friend from the same ethnic background is able to make important connections for the family to needed services. In some cases, no such network is available to newcomers. In all cases, professionals need to engage in greater community outreach. Agencies need to provide access to appropriate translation supports, and to ensure that they are offering culturally sensitive services. Professionals need to do their part to ensure that newcomer families receive the appropriate assistance, so that all children in their communities will thrive.

For more on cultural considerations go to Section 6 Supporting Parents and Professionals